Moving inwards, we can apply this to the mind.

The mind is like space, there's room in it for everything or nothing. It doesn't really matter whether it is filled or has nothing in it, because we always have a perspective once we know the space of the mind, its emptiness.

Armies can come into the mind and leave, butterflies, rainclouds or nothing. All things can come and go through, without our being caught in blind reaction, struggling resistance, control or manipulation.

So when we abide in the emptiness of our minds we're moving away we're not getting rid of things, but no longer absorbing into conditions that exist in the present or creating any new ones. This is our practice of letting go. We let go of our identification with conditions by seeing that they are all impermanent and not-self.

This is what we mean by vipassana meditation.

It's really looking at, witnessing, listening, observing that whatever comes must go. Whether it's coarse or refined, good or bad, whatever comes and goes is not what we are. We're not good, we're not bad, we're not male or female, beautiful or ugly.

These are changing conditions in nature, which are not-self. This is the Buddhist way to enlightenment: going towards Nibbana, inclining towards the spaciousness or emptiness of mind rather than being born and caught up in the conditions.

Now you may ask,

`Well if I'm not the conditions of mind, if I'm not a man or a woman, this or that, then what am I'?

Do you want me to tell you who you are?

Would you believe me if I did?

What would you think if I ran out and started asking you who I am?

It's like trying to see your own eyes: you can't know yourself, because you are yourself.

You can only know what is not yourself and so that solves the problem, doesn't it?

If you know what is not yourself, then there is no question about what you are.

If I said,

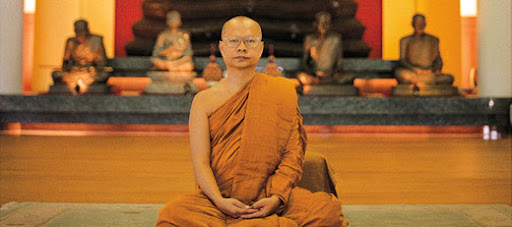

"Who am I? I'm trying to find myself,' and I started looking under the shrine, under the carpet, under the curtain, you'd think, `Venerable Sumedho has really flipped out, he's gone crazy, he's looking for himself.' `I'm looking for me, where am I?' is the most stupid question in the world.

The problem is not who we are, but our belief and identification with what we are not.

That's where the suffering is, that's where we feel misery and depression and despair.

It's our identity with everything that is not ourselves that is dukkha.

When you identify with that which is unsatisfactory, you're going to be dissatisfied and discontented it's obvious, isn't it?

So the path of the Buddhist is a letting go rather than trying to find anything. The problem is the blind attachment, the blind identification with the appearance of the sensory world. You needn't get rid of the sensory world, but learn from it, watch it, no longer allow yourselves to be deluded by it.

Keep penetrating it with Buddha-wisdom, keep using this Buddha-wisdom so that you become more at ease with being wise, rather than making yourself become wise.

So at this time you have nothing else to do except be wise from one moment to the next.